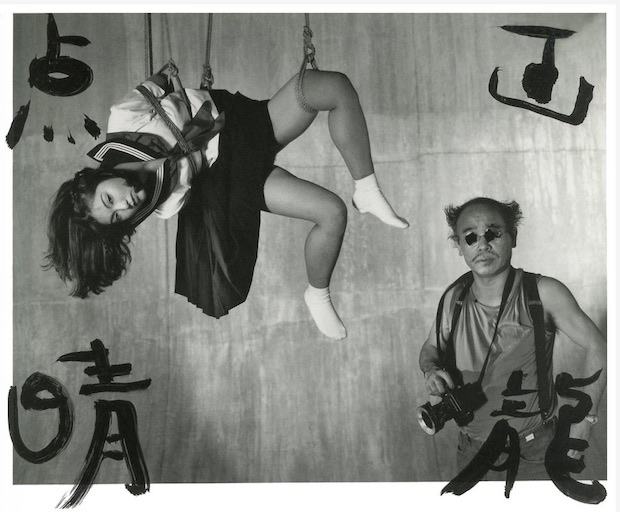

The prolific and award-winning photographer Nobuyoshi Araki has become one of the first major cultural figures in Japan to become embroiled in the MeToo movement.

KaoRi, who was once frequently named as Araki’s “muse,” has come forward with a note.mu blog posting (in Japanese) on April 1st that accuses the 77-year-old of exploiting her during the years from 2001 to 2016 when she was his model.

She says that she was forced to take part in shoots while strangers came into the studio to watch. She claims she was not always paid for her work and that her approval was not sought for the way in which images of her nude body were used. For example, she says she was not told that photographs of her would be presented part of a series provocatively titled “Kaori Sex Diary.” Likewise, the photographer and his management company pursued a commercial agenda by releasing photo books and DVDs of her images, but she was not consulted.

While much of this is typical of the relationship between photographer and model that is arguably always exploitative to some fundamental degree. Terminology is knotty and imperfect, but, without any intention to belittle her experience at all, it might be ventured that KaoRi’s case is more one of power harassment and commercial exploitation than the “conventional” assault and abuse that many female models face at the hands of renowned male photographers. The situation was particularly aggravated since there was no contract or formal agreement between KaoRi and Araki’s company, which meant she had no control.

However, one key distinction is the adult nature of the images, which consistently turned her nude body into a product for monetary gain, and how KaoRi’s accusation comes in the wake of those (more serious ones, it should be said) against the likes of Terry Richardson, Bruce Weber, and Chuck Close.

KaoRi claims that she requested Araki address her concerns but her pleas were either ignored or fobbed off. She wanted to stop modeling for him, though was then pressured to continue because by then her image had become so central to his “brand” and, thus, the livelihood of his company. Ultimately, the anguish caused by their professional relationship led to health issues. In addition, the way she was presented to the world meant she attracted a stalker, resulting in the need to move to a home with better security. Araki did not, she says, offer her sympathy or support during that stressful time. The article also details the legal pressure she received from his company through what was effectively a cease-and-desist letter after she demanded improvements to her treatment in early 2016. Eventually, she was fired in June that year.

KaoRi does not, it should be stressed, accuse Araki of any sexual assault and there is no suggestion of direct sexual contact between the photographer and his model. At the time of writing, Araki’s company has yet to make an official response.

Araki is celebrated as a pioneering and visionary force in Japanese photography, especially for such landmark series as Sentimental Journey (1971). He is probably best known, however, for his erotic photography, which blurs the line between pornography and high art. A major exhibition, “The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Work of Nobuyoshi Araki,” which includes images of KaoRi, recently opened at the Museum of Sex in Amsterdam, running through August 31st, 2018.

Many have previously noted the problematic nature of Araki’s popularity and veneration as a photography legend for “art” that is overtly provocative and troubling in its depiction of women. Is his explicit output merely the self-indulgence of a “dirty old man” and the male gaze, or does it have something genuine to say about Japan or the human condition? Would Araki enjoy such success in the West if he used white women rather than Asian models?

It is a thorny and ongoing debate, boosted by a plethora of articles about the current exhibition in Amsterdam, and this new development will only further fuel the discussion. Unsurprisingly, it’s not even the first time Araki has faced ethical accusations from a model. Priscilla Frank explained an earlier case in an article in the Huffington Post in February that:

By most known accounts, the women in Araki’s photos fully consented to the sexual situations and interactions depicted therein. There is one notable exception, which MoSex brings to light: In a Facebook post this past August, a woman claimed that Araki touched her inappropriately on a commercial shoot for a Japanese teen magazine in 1991, when she was 19 years old. (The woman, who never pursued legal action due to fear of professional repercussions, asked the curators not to disclose details of her identity or the alleged incident.)

KaoRi’s allegations quickly attracted some attention on social media and an article on Cinra, an online magazine that focus on arts and culture. However, there was little mainstream press response, though that is likely to follow now that the fashion model and actress Kiko Mizuhara has posted a reaction online.

Mizuhara, who has also worked with Araki in the past, praised KaoRi’s bravery in coming forward and also noted her own similar experience when doing a semi-nude shoot for a corporate client. She found herself treated like an object to be watched by dozens of male strangers who intruded on the shoot while she was at her most vulnerable. Mizuhara is one of the biggest names in the industry, so has nothing to fear from coming out in support of a fellow model. That being said, she was discreet enough to use the Stories function on Instagram that deletes content after 24 hours.

The MeToo movement has yet to gain significant traction in male-dominated Japan, though there has been at least one very prominent case: that of the journalist, Shiori Ito, who was allegedly raped in 2015 by a senior fellow journalist (and friend of the prime minister). Police dropped the case and Ito was forced to go public, write a book, and file a civil suit in order to pursue justice amid accusations of political pressure.

On the other hand, South Korea has been rocked by several high-profile cases, not least the acclaimed film director Kim Ki-duk, who has been accused of rape and assault by several women.

It is an open secret in Japan that the casting couch is very well entrenched in the music idol, gravure (glamor modeling), and other parts of the entertainment industry. With some exceptions, no major performers or entertainers have come forward with experiences of harassment. The reasons for this are complex, though the way the management agency (jimusho) system works is possibly one factor. But perhaps it is just a matter of time before allegations trickle out. In fact, a scandal with similarities to MeToo has already hit Japan’s infamous yet lucrative adult video industry, where multiple female performers have come forward with accusations of coercion that have led to arrests and trials.