You might have thought that communism was safe from mascots but then you’d be wrong.

As shared by Matt Alt, the Japanese Communist Part has its own kawaii characters now, the so-called Proliferation Bureau, including a snazzy expensive-looking website.

The cast of eight mascots include Otento-sun, a sun who is fighting nuclear power, a purse called Gamagucchan who looks after tax reduction for ordinary households, Shiisa, an Okinawan lion dog (shisa) in charge of the issue of US bases in Okinawa, and Kakusan (“proliferation”), the leader.

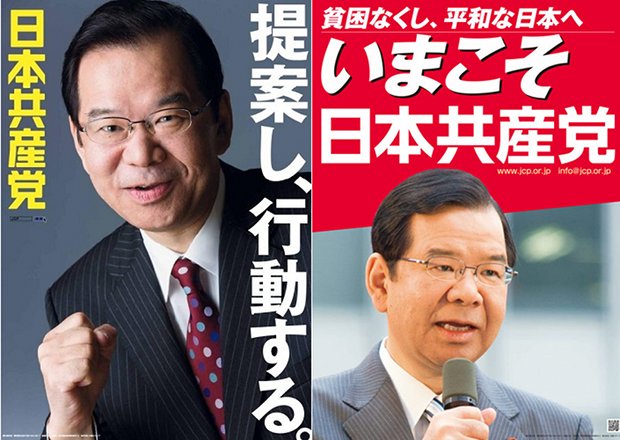

The characters were used as part of the campaigning for the recent election and communist cosplay could be seen around Japan, with supporters dressed up as the characters. The idea is to make politics easier to understand and engage potential voters via digital media. (The recent elections also marked the first time that candidates were allowed to use the Internet in campaigning, indicating the things are gradually changing.) Before scoffing, we should remember that the turnout for the recent Upper House election fell several percent — so anything that raises the profile of genuine politics can’t be a bad thing.

The JCP is actually not a communist party in the true sense of the word. It does not aspire to implement communal ownership of property, nor has it done so for decades. Perhaps the most radical thing it might do if it ever gained a majority might be to re-nationalize a few things. After the war, having been heavily persecuted during the militarist era and then again by the US occupation authorities, it still tried to

It sent guerilla activists into the mountains to try to kick-start local subversion and rebellions against dam projects, but all was to no avail. It realized it was never going to get elected this way and official renounced armed struggle. It named its new identity “lovable communism” (aisaseru kyosanshugi).

Since the late Fifties it has never advocated subversive actions and its participation in the Anpo struggles in 1960 and 1970 were peaceful, as were its contribution to the anti-Vietnam War campaigns. However, for this it earned the ire of student radicals and other groups, especially for its failure to assist properly in the protests against Narita Airport and the controversial docking of a US submarine in Sasebo in 1968. A student group split from its youth movement in the late Fifties and thus began the New Left/Old Left dichotomy that essentially defined Japanese left-wing politics after the war.

Today the JCP is doing rather well. Its membership and subscription to the Akahata have risen in recent years with the fears of growing disparity in Japan since the Lost Decade began, fears which were then further exasperated by the worldwide recession that saw lots of temps laid off and soup kitchens in Tokyo. In the recent local government elections and Upper House election it made small but significant gains.

However, its protectionist policies might be baffling to some. For example, it is opposed to the increasing of consumption tax — surely the most universal and fair way to raise money for the burden of the aging population — and is against the TPP trade tariff agreement. (Actually, as a more learned commentator has pointed out, the inherent conservatism of all the parties that form the ostensible opposition to the ruling LDP, a bone fide conservative party, are all lacking in progressive, active policies.)

It should also be noted that the JCP apparently hired an ad agency to design the mascots, which hardly smacks of trying to pulling down the pillars of capitalism.